Seventeen pan-European higher education alliances focused on working with industry, community and embracing alternative education models are benefiting from EU funding which comes on stream this month. What could they achieve?

“We are all very optimistic about it. We see it as a great opportunity to create a truly European university model,” says Seán Hand, deputy pro-vice-chancellor of the University of Warwick in the UK.

He is enthusing over a newly forged bond with partner universities in Brussels, Barcelona, Gothenburg, Paris, and Ljubljana.

The alliance, called EUTOPIA, is one of 17 others supported by the EU – each European University alliance receives €5 million in the first three years and will work to become models of European integration: “inter-university campuses” around which students, doctoral candidates, staff and researchers can move seamlessly.

“We would have pursued many of the planned cooperative projects anyway,” explains Luke Walton, international press manager at Warwick. “But the EU call has encouraged us even more to further enhance our focus on Europe as a key part of our internationalisation strategy.

“It offers a framework, some funding and a public platform to put a sustainable collaboration in place.”

Bartosz Brozek in Kraków is driven by the same pioneering spirit. As vice-dean for international relations, he manages the Jagiellonian University’s projects within the seven-member group UNA Europa.

“The EU money is not even essential,” he stresses. “All of us are committed to working together as one future university. And we are starting by creating a common identity.”

The origins

The enthusiasm for the ‘European Universities Initiative’, launched by the European Commission in late 2018, was huge from the very beginning. A thousand participants, internationalisation officers, vice-rectors, ministerial delegates and representatives of research organisations, joined the information session in Brussels before Christmas either in person or via a video link.

Over 300 institutions from 31 countries — that is one in 10 of the approximately 3,000 universities in the European Union — had formed 54 networks and submitted their proposals by February. Eventually 17, comprising 114 institutes, were selected in June.

The European Universities project, first pronounced in autumn 2017 by the newly elected French President Emmanuel Macron in his Sorbonne speech, has been hailed as nothing less than a “renaissance of the European spirit.”

“He didn’t have a very precise agenda,” recalls François Taddei, who is a counsellor for the 4EU+ alliance of six partner universities — Charles, Heidelberg and Sorbonne Universities, and the Universities of Copenhagen, Milan and Warsaw.

“But he is someone who deeply believes in Europe and in education, and who believes that universities are the place where discussions can be happening. He was clever enough not to over-prescribe, feeling that there was an interesting potential there.”

The idea originated, according to education journalist Jan-Martin Wiarda, in the European department of the Elysée Palace, and had to be elaborated by the research ministry. Some in the French government, says Wiarda, claim that Macron’s wife Brigitte Trogneux inspired it.

Twenty French universities will receive €100 million over 10 years

Higher education and research minister Frédérique Vidal said in retrospect: “We already agreed in the election campaign that universities and research institutions will play a central role in reconciling citizens with Europe.”

Making it in the first round

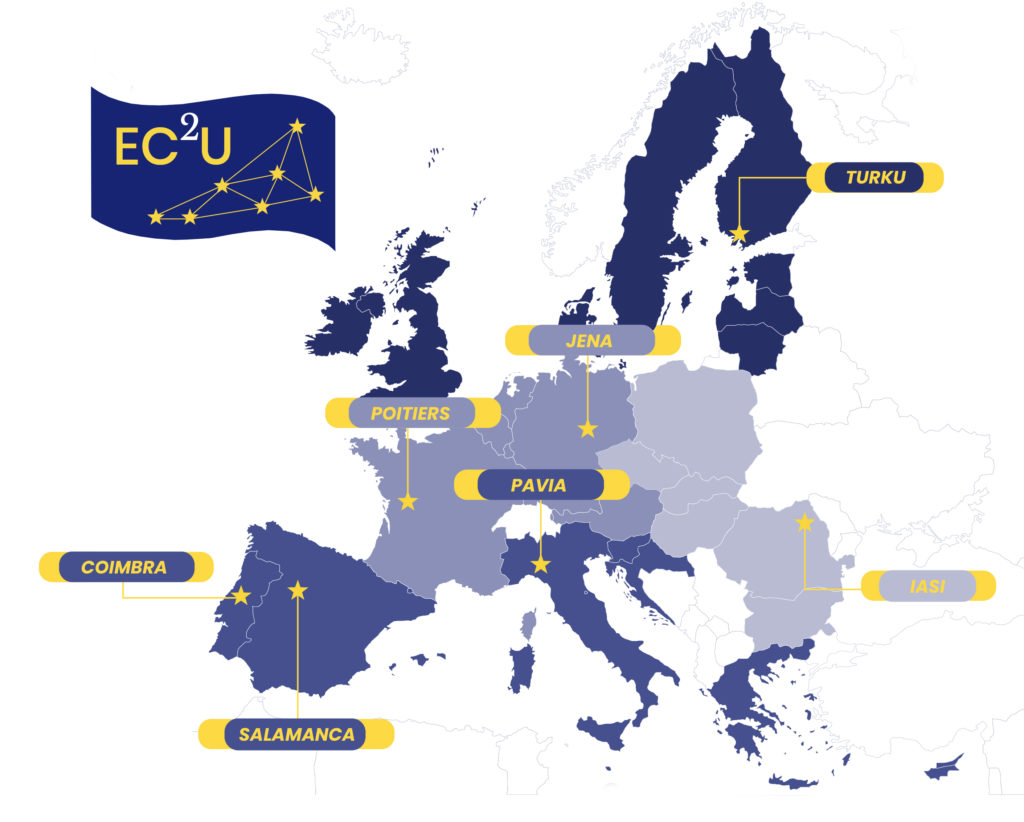

“We lost out in the first round by one point,” explains Ludovic Thilly, professor at the University of Poitiers and Executive Vice-Rector in charge of European affairs. He coordinates the European Campus of City-Universities, or EC2U, with Coïmbra, Iasi, Jena, Pavia, Salamanca, Turku and Poitiers in the boat.

“Our EC2U Alliance was ranked 18th, so that was very frustrating… Fortunately, we got a score of 80/100, i.e. we reached the score of excellence, and thus we are supported by the French government. This will greatly help with preparing the best resubmission.”

The selection was made by an evaluation committee, based on the advice of 26 independent external experts whose names were not made public. Each proposal was assessed by three of them against the five necessary criteria: relevance, geographical balance, quality of the proposal, quality of the cooperation arrangements, sustainability & dissemination.

Thilly, who recently attended an EU information session in Brussels, said the Commission considers funding alliances selected in the first and second round for a three-year period with the possibility to apply for a four-year extension.

After that, they are supposed to be self-sustaining. From 2021, when the Initiative becomes part of the Erasmus+ program, subsidies for four years with the possibility of a three-year extension are under discussion.

The financing

“Five million euros for three years per consortium is not very much,” Frank Petrikowski, a policy officer for the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research, BMBF, told ESNA European Higher Education News in Berlin. The first mentioned budget was €30 million, it was raised to €60 million and finally set at €85 million for 17 – instead of 12 – chosen consortia.

He hopes that the European Universities will be “a counterweight to Harvard and Stanford”

“It is planned to go even further to €120 million in the second round,” he reveals. “€1.3 billion has been earmarked as a separate pillar of the Erasmus+ program in the forthcoming MFF from 2021 to 2027.”

Secondly, some governments are committed to provide additional money. French and German universities scored highest in the first round of the competition, appearing in 16 and 14 successful alliances respectively.

Paris will support “very well evaluated projects” with a focus on “research and innovation” as well as “other activities which are not eligible for European funding on national territory.” Twenty French universities will receive €100 million over 10 years. Among them are four universities; the above-mentioned University of Poitiers, as well as Orléans, Troyes, and Lille — whose alliances were unsuccessful in the first round.

The Germans have set up a national support programme of €7 million over three years; this also includes universities that didn’t win the first bid and might even not win the second, but that scored high in the Commission’s evaluation.

Rattling the rankings

Harald Kainz, rector of the Technical University of Graz, which is a member of the university alliance ARQUS, hopes that the European Universities will be “a counterweight to Harvard and Stanford.”

Patrick Aebischer, former President of the École polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), went even further, saying at a conference in Munich that the Initiative should focus on a few top universities in order to create a European Ivy League after the American model.

Olga Wessels, Head of the Brussels’ Office of the ECIU University — the biggest of the alliances with now 14 member universities — makes no bones about it: “Especially after Brexit when the UK is leaving the EU, if you look at the rankings, there are not many highly ranked European universities. So we need to build competitiveness of the universities.”

So far, the advantage of internationally high ranking European universities is marginal. Among the 114 alliance members successful in the first round of the programme, only 18 are in the top 200 of the Shanghai ranking, 25 in the QS ranking and 26 in the Times Higher Education ranking.

Can the incentives for merging ever be big enough for a university to give up its autonomy? Or, under what conditions would international ranking companies consider a European University one institution? Phil Baty, editor of the THE World University Rankings, told ESNA: “It is very unlikely that we would treat such a consortium or alliance as a single entity—we tend to look at the legal entity when considering how to rank organisations.”

Kinds of innovation

The call’s specifications were patched together by the EU agency EACEA in a consultation process with the higher education and research sector. Unsurprisingly, they bear the mark of research-intensive universities with strong industry relations in need of ‘innovation’, ‘excellence’ and ‘entrepreneurship.’

An interesting plan of YUFE is furnishing special homes where students can live for free during their stay

The networks have been given catchy names such as EUTOPIA for European Universities Transforming to an Open, Inclusive Academy for 2050, or EDUC, short for European Digital UniverCity, or UNITE! as an acronym of University Network for Innovation, Technology and Engineering.

ECIU University, the European Consortium of Innovative Universities, is less catchy but interesting for its statement that it “is determined to change the way of delivering education from degree-based to challenge-based”.

Beyond the compelling names, there are many pedagogically interesting projects, of network-building experiments and of activities that involve students, citizens and local companies.

One is a multi-campus joint master’s course of the alliance CIVICA. The course forms “European knowledge-creating teams” which concentrate on four research topics.

The alliance with members from France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Romania and Sweden, including the private business school Hertie School of Governance in Berlin, also organises a trans-European arts and sports tournament.

CharmEU includes the University of Barcelona and Montpellier, Utrecht and Eötvös Loránd University and Trinity College Dublin; they are not the only alliance planning multilingual courses and language-learning support for the participating students. But they are particularly ambitious in exploring exemplary collaboration models—a joint-governance model, guidelines for joint degrees and an open science agenda.

Alternative education

The above-mentioned ECIU alliance wants to experiment with alternative educational formats, offer micro-courses, micro-credits, a “competence passport”, and organise “pop-up labs.” These approaches point at diverse learning paths, where students participate in composing their curricula, and skills can be recognised across borders.

The alliance YUFE of eight “young universities” is interesting for its associated partners — the NGO Kiron that builds an online learning platform for refugees, the Adecco staffing agency, the testing organisation ETS Global, and a European association of small and medium-sized enterprises.

An interesting plan of YUFE is furnishing special homes where students can live for free during their stay and in close proximity with local residents.

EC2U, hoping to be successful in the second round, also puts emphasis on community connections. “Our ambition,” says Thilly, “is to deepen the connection with the local communities of the cities we are rooted in.

“We want to involve the municipalities and citizens into the university life, for instance through open conferences, workshops and summer schools.”

Coïmbra and Poitiers have already started by linking their students’ music and arts festivals and by setting up support schemes for young student artists aimed at improving their professional integration.

This article was first published in The Pie News, on November 15, 2019